Memory, Dirt and Reflection

Just the idea of spring teases up desire in the gardener (and the would-be gardener). The onset of local flower shows, the arrival of glossy seed catalogues in the mail, even the sinking of shoes in the sucking mud under a stubble of leftover grass are enough to waken desperate longing to dig, turn earth over, plant things way before the last danger of frost because you can’t wait. Let’s start things growing again, for the love of God!

What to do if you share this pent-up swell of yearning but there is still snow coming down?

Aside from starting seedlings indoors, preparing beds, leafing anxiously through said glossy catalogues and eyeing the frisky squirrels, rabbits and other critters with concern, you may also want to find solace in community. And you might just find that community in a book.

One of my favorite books ever takes me deep into the community of – not your corner nursery garden store variety of landscape planters – but gardeners whose histories, whose ways of life, and often very souls, are constructed and reconstructed with every season of digging, planting, wedding and harvesting.

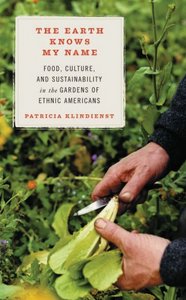

The Earth Knows My Name: Food, Culture and Sustainability in the Gardens of Ethnic Americans by Patricia Klindienst is luminous.

Klindienst is a master gardener, but she is also a masterful listener and observer. In this book, she crisscrosses the United States to tell the stories of nine “ethnic” gardens and the people who nurture them. She takes her initial inspiration from The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Italian immigrants who in 1927 were put to death for murder or anarchy or both, or perhaps just for being immigrants. Vanzetti, in particular, was a lyrical gardener, and his ability to fly on the wings of garden memory away from his fate, intertwines with her own history as the descendant of Italian immigrants.

That metaphor of the immigrant gardener putting down roots, nurturing and being nurtured by the new land, takes her to New Mexico, where native Americans still do things their way, no matter who else thinks they are in charge; to the Gullah islands of North Carolina where the descendants of former slaves still plant freedom;. Khmer refugees find relief and refuge in a garden in Massachusetts, the same state where uprooted Nuyoricans find connections in urban gardens and an Italian couple undoes political upheaval in self-made sanctuary; in Connecticut ancient and sacred corn is returned to native Americans from those who had taken their land in the colonial days; a Punjabi garden grows in California; and a Japanese American berry farmer again tries to preserve farmland in Washington State, decades after his family first lost it in WWII relocations, only this time he has a Polish American vintner to help him.

It’s hard to say which story is more touching; why would you try to choose, when they are all equally meaningful?

So, as you gear up for a new growing season, you may want to dig into The Earth Knows My Name, for kinship, for inspiration, for validation and for something satisfying and fulfilling to do as you wait for the sun to rise so you can get out there and write your own story in the dirt.

By Natalia de Cuba Romero

(The Earth Knows My Name: Food, Culture and Sustainability in the Gardens of Ethnic Americans by Patricia Klindienst 2006 Beacon Press)